Ulster-Scots, or Scotch-Irish as they are also known, were Scots who emigrated to the Irish province of Ulster from the Scottish Lowlands beginning in the early 17th century, initially as part of a crown-sponsored plan to settle Protestants on lands confiscated from Ulster's Catholic nobility. A second wave of Scottish emigration to Ulster followed a severe famine in Scotland in the 1690s. According to one researcher, our line may have come from around the Scottish village of Ochiltree in Ayrshire.

[Click on any of the images to see them larger. Click on any orange text to read a link about the place.]

Various databases, including the extensive genealogical database compiled by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (a Mormon project to categorize as many lineages as possible), includes an intriguing record for a James Smith, who was christened in Ochiltree in August, 1646. According to that record, he married a woman named Janet Robb on June 8, 1671. Even today, Ochiltree only has about 1,200 people but it will take more research to determine whether this could have been a relation.

Following Ireland's Nine Years' War, in which Gaelic chieftains fought unsuccessfully to throw off English rule, the remaining resistance left Northern Ireland in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to regroup and return with Spanish support - an event known as the Flight of the Earls. With the opposition gone, King James I subsequently pursued a policy of 'plantation,' opening the lands that the Earls had left behind to settlement by Protestants loyal to the crown.

James, who was king of Scotland as well as Ireland and England, granted lands to both English and Scottish nobles, who in turn were expected to settle tenant farmers from their own estates on their newly acquired Northern Ireland properties. Settlers had to be Protestant and English-speaking. Those from the Scottish Lowlands were Presbyterian and spoke Scots, an English dialect distinct from the Scottish Gaelic spoken in the Scottish Highlands. This was the genesis of 'the troubles' that plague Northern Ireland to this day.

The first wave of Scots to settle in Ulster were from Ayrshire, recruited in 1606 by two Ayrshire Scots - James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery – who had been granted land in Ulster by the king. Hamilton’s share of the territory included the River Bann and the area around Coleraine, where we know neighbors of the Smiths in New Hampshire once lived.

If we accept the theory that our ancestors were from Ayrshire, it is not hard to imagine that our forefather took part in this migration and settled near Coleraine.

By the end of the century, the Presbyterian Scots in Ireland were suffering from laws which favored Anglicans, who were mainly the descendants of English settlers. The Woolens Act of 1699, prohibiting the export of linen cloth, dealt a crippling blow to the Scottish weaving industry in Ulster. Legislation restricting Presbyterians from holding office and exorbitant increases in rent squeezed the Scotch-Irish further. By 1710, most of the farm leases granted to the Scottish settlers in the 1690's had expired and were up for renewal. Finally, when a fourth successive year of drought ruined crops in 1717, serious preparations for migration began.

In his 2001 book, "The People with No Name: Ireland's Ulster Scots, America's Scots Irish, and the Creation of a British Atlantic World," Patrick Griffin wrote that "between 1718 and 1775, more than 100,000 men and women journeyed from the Irish province of Ulster to the American colonies. Their migration represented the single largest movement of any group from the British Isles to British North America during the eighteenth century. In a first wave beginning in 1718 and cresting in 1729, these people outnumbered all others sailing across the Atlantic, with the notable exception of those bound to the New World in slave ships."

Some of those early emigrants settled in New Hampshire in a place originally called Nutfield because of the abundance of chestnut, walnut and butternut trees there. They built a town, which they called Londonderry after Londonderry in Ulster, from which they had come. An 1851 history of Londonderry, New Hampshire, by Edward Lutwyche Parker, says that they came from the valley of the river Bann, "in or near the towns or parishes of Coleraine, Ballymoney, Ballywoolen, Ballywatick and Kilrea."

The small band that settled in Nutfield, later called Londonderry, brought potatoes with them from Ireland and planted them in the town's Common Field. This is said to be the first cultivation of the plant in the colonies. Nutfield's Scotch-Irish were also linen weavers and Londonderry linen became so well known in colonial America that the town passed a law in 1748 requiring that all linen woven there be marked with a seal bearing the town name in order to discourage counterfeiting. This is said by some to be the first trademark in the New World.

In fact, the Nutfield settlers were the first major group of Scotch-Irish to emigrate from Northern Ireland. They left under the leadership of Rev. James MacGregor or McGregor, after petitioning the Massachusetts Bay Colony governor, Samuel Shute, for land in 1718.

Among those who signed that petition are several Smiths, including two Samuel Smiths and two James Smiths, though we have no way of knowing if any of them are of our line. Nonetheless, there is an intriguing trail of citations that trace the names Samuel Smith and James Smith to Londonderry, New Hampshire.

A brief history by the Londonderry Historical Society tells us that five shiploads of people left Ulster for the New World under Rev. MacGregor's guidance:

One group remained in Boston, one group settled in Dracut and Andover and a third group ventured north to what is now Portland, Maine. A harsh winter and low provisions forced the third group to retreat south to Haverhill, Massachusetts, where they heard of a twelve square mile area "abound with nut trees." Sixteen families left Haverhill for Nutfield in 1719 and on June 21, 1722, established a charter for the Township of Londonderry.A Samuel Smith came to the New World in 1719 on board the "Elizabeth," a ship that had been part of the 1718 migration. The ship's captain was Robert Homes (or Holmes), who was born at Stragolan, County Fermanagh, Ireland, in 1694.

Robert Homes' father, William Homes, was a Presbyterian clergyman who had travelled to the New World as a young man and met the renowned Boston clergymen, Increase Mather and his son, Cotton Mather. William Homes returned to Ireland but eventually emigrated with his family to Boston in 1714. The next year, he became the congregational minister of Chilmark, Martha’s Vineyard, where he remained until his death in 1746.

In April 1716, William Homes' son, Robert, married Mary Franklin, a sister of Benjamin Franklin. Robert became the mate to Alexander Miller with a share in the ship “Mary and Elizabeth.”

By November 1717, Rev. Homes and his son were in correspondence with Cotton Mather, who was recruiting Scotch-Irish migrants to settle in New Hampshire and Maine in hopes of creating a buffer between the hostile Indians and the settled towns of Massachusetts. Robert was instrumental in spreading the word back in Ireland. Edward Lutwyche Parker, in his 1851 “History of Londonderry,” gives this account:

A young man named Homes, son of a Presbyterian clergyman, first brought reports to the people in Ireland of opportunities in New England. This was probably Captain Robert Homes, son of the Rev. William Homes; he had an unusual opportunity for intercourse with his father's former parishioners through his voyages to Ireland. In 1717 two men with names later significant in the Worcester and Falmouth settlements, called to see the minister at Chilmark; they were John McClellan and James Jameson. Three weeks later (November 24th) Mr. Homes writes in his diary: "This day I received several letters, one from Doctor Cotton Mather, one from several gentlemen proprietors of lands at or near to Casco Bay, and one from son Robert.Charles Knowles Bolton, in his 1910 “Scotch Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America,” refers to Parker's account with an interpretation:

The above quotation points strongly to a conference held at Boston in November between Captain Robert Homes, recently from Ireland and interested in transporting Scotch Irish families, the Rev. Cotton Mather, eager to see the frontiers defended by a God-fearing, hardy people, and the third party to the conference, the men who were attempting to plant settlements along the Kennebec. They must have talked over the project for a great migration (they all had written to the minister at Chilmark), and undoubtedly Captain Robert Homes sent over letters and plans to friends at Strabane, Donaghmore, Donegal and Londonderry. Perhaps no one in Boston had so many relatives among the clergy in Ulster, and as a sea-captain he had a still further interest in the migration. Robert himself sailed for Ireland April 13, 1718, and returned "full of passengers" about the middle of October.The ship on which Robert Homes returned from Ireland was the “Mary and Elizabeth.” The Boston News-Letter recorded it as 45 tons and arriving in October carrying linen and 100 passengers. It was one of about 15 ships that arrived that year from Ireland and is sometimes counted among the "five ships" said to have brought the Bann Valley emigrants to the New World.

After they arrived, some unverified accounts say the captain, Alexander Miller, bought a farm in Saco, Maine, and sold his share in the ship to Homes. According to one of those accounts, Homes became the captain and rechristened the ship the “Elizabeth.” In any case, Homes returned to Ireland and carried a second load of Scotch-Irish emigrants, including a Samuel Smith, to Boston in 1719.

Smallpox broke out on the ship and about 30 of its 150 passengers were "warned out" of Boston when they arrived.

A Samuel Smith is listed among those passengers of the 'Elizabeth' who were "warned out," or refused entry to Boston in November 1719. The list includes two of the original proprieters of Londonderry, New Hampshire: Robert Doke and Abraham Holmes.

Some of those that were "warned out" were sent into quarantine at a pesthouse that had been built for the purpose on Spectacle Island, in Boston harbor, in 1717. It's not clear where the others were housed, though the Boston selectmen ordered that they be provided with fresh mean, greens and firewood.

Ulster Scots continued to arrive from the Bann Valley in subsequent years. The following account about Archibald Stark is from a history of the Jelke and Frazier and Allie Families, written by L. Effingham De Forest in 1931:

In 1720 Archibald Stark, in company with a number of other Scottish Presbyterians, started for New England to join some of their neighbors and co-religionists who had settled at or in the vicinity of Nutfield, New Hampshire (later, Londonderry, New Hampshire). The vessel on which they sailed was overcrowded and the voyage was a very uncomfortable one, even before the plague of smallpox broke out. Several passengers died, including the children of Archibald Stark. When the ship reached Boston, it was not permitted to discharge its passengers because of the smallpox on board, but was sent to the desolate coast of Maine, where the present town of Wiscasset stands, to spend a year in quarantine. There the winter was endured with much suffering. It was not until the summer of 1721 that the survivors of the group of settlers reached their new homes in New Hampshire.

A William Smith is listed beside Archibald Stark among the proprietors of Londonderry at its incorporation in 1722 but nothing more is known of him.

George F. Willey, in his 1869 Book of Nutfield, noted that there was a James Smith with land in the town, and John Goffe, Londonderry's first clerk, recorded that this James and his wife 'Jean' bore a son named William in 1715. New Hampshire Vital Records, meanwhile, record the birth in Londonderry of a Samuel Smith to James and 'Joan' Smith on March 29, 1720.

Our line, however, is not related to this James or his sons William and Samuel. James' son Samuel died in September, 1752, and is buried near the grave of his father, who died a year later. A direct descendant of William, meanwhile, carries a different Y-DNA haplotype than does our line, meaning we are not related.

There is no Samuel Smith on the original Londonderry proprietor's list, but a Samuel Smith does appear in Londonderry records in subsequent years.

In the 1730s, Londonderry split over rival pastors and some of its members established a new parish in the western part of the town. Eventually, the split divided the town into Londonderry in the west and Derry in the east. A Samuel Smith appears on various petitions related to the formation of the West Parish. He may have been the father or an uncle of our Samuel Smith, though, again, there is no way of knowing what relation, if any, he has to our line.

From Londonderry, the early immigrants branched out in various directions looking for undeveloped land. Some settled near the current town of Dunbarton in the late 1740s and, in 1751, a group led by Archibald Stark was given a grant to form a town there. They called it Starkstown. The name was changed in 1765 to Dunbarton, after Dumbarton, Scotland (just south of the famous Loch Lomond), where Archibald Stark was born.

Among the other original settlers of Starkstown was John Stinson, also a Scot from Londonderry, Ireland, and the head of a prominent family that would have close dealings with the Smiths. [I have color coded the various John Stinsons so that they can be differentiated and identified using a chart below]

Other families with whom the Smiths were associated also came in the early wave of Ulster-Scot migration and settled in Londonderry, Derry or Dunbarton.

Our Samuel Smith and his wife may have been born in New Hampshire to families that arrived in that initial migration or they may have moved to New Hampshire from elsewhere in the colonies. Given that there was a Samuel Smith on board the "Elizabeth" with men who were among the original proprietors of Londonderry, and that our younger Samuel Smith was among the early settlers of Starkstown, it is not hard to imagine that the younger Samuel Smith is related to the Samuel Smith who emigrated from Ireland in 1719.

Whichever the case, it is almost certain that Samuel Smith and his wife Elizabeth were Scotch-Irish Presbyterians with roots in the Scottish Lowlands.

Elizabeth was born on July 9, 1729, though we don’t know where. Our Samuel was probably born about the same time.

In 1753, "Samuel Smith of Starkstown" bought Lot 12 in the "2nd range" from Caleb Page for "160 pounds, Old Tenor," according to Dunbarton records. He built a house on the 100-acre lot "on old 4-rod road (now abandoned)."

This is the first documentary evidence that we have of our Samuel Smith. As was the custom in that day, the town was laid out with rectangular lots arranged in a row, or range.

"Old Tenor" refers to the paper money issued by the Massachusetts and New Hampshire colonial governments prior to 1742. The "bills of credit," as they were known, depreciated rapidly in value and new bills, or "new tenor," were issued to reflect the depreciation.

The "4-rod" reference is the width of the road, a rod being a unit of length in the English system originally fixed by King Edward I in 1303. It is equal to about 16 ½ feet, so a 4-rod road is 66 feet wide. Road widths are still measured this way.

Caleb Page was a colorful character, according to a Merrimack County history:

In 1740 he married a widow Carleton, of Newburyport, who weighed three hundred and fifteen pounds. She, together with a huge arm-chair, now in the possession of the Stark family, had to be carried to meeting on an ox sled.In 1751, according to the history, Page sold his lands in Atkinson, New Hampshire, for his wife's weight in silver dollars, and relocated to Dunbarton.

The country was then infested with Indians; and his daughter Elizabeth, who later became the wife of General John Stark of Revolutionary fame, often stood, musket in hand, as guard at the rude block-house.Well, happy for the white folk, at least.

Caleb, who is said to have had a noble and benevolent spirit, had ample means to indulge his generous impulses. His money, comprising golden guineas, silver crowns and dollars, was kept in a half-bushel measure under the bed. He owned many slaves. His house was the abode of hospitality and the scene of many a happy gathering.

This is Caleb Page's house at Page's Corner in Dunbarton. His daughter, Gen. John Stark's wife, stayed here throughout the Revolutionary War.

This is Caleb Page's house at Page's Corner in Dunbarton. His daughter, Gen. John Stark's wife, stayed here throughout the Revolutionary War. The house that Samuel Smith built on the land he bought from Caleb Page still stands. This page is from Harlan Noyes' 2004 book, "Where Settlers' Feet Have Trod."

The house that Samuel Smith built on the land he bought from Caleb Page still stands. This page is from Harlan Noyes' 2004 book, "Where Settlers' Feet Have Trod."When originally built by Samuel Smith, the house was two stories tall and one room deep, with a central chimney that contained two fireplaces on each floor.

This is a picture of the house taken in June, 2010. Roger Smith is standing in front. The owners weren't home.

This is a picture of the house taken in June, 2010. Roger Smith is standing in front. The owners weren't home.

This is the house in which Sarah Kinney Smith was born.

Alice M. Hadley, in her 1976 book, "Where the Winds Blow Free," writes that:

"This farm was settled in very early times by Samuel Smith; then by John Stinson, son of Samuel Stinson, one of the first settlers. The house was built in part before the Revolution ... The house has been changed so many times it is hard to know what its first shape was.Ms. Hadley was apparently mistaken in her identity of John Stinson, as he was son of John Stinson Sr., one of the first settlers in the town. Samuel Stinson was a brother. Ms. Hadley also writes in her book that Samuel Smith owned the 100 acres of Lot 17, 3rd range, which he mortgaged to Jeremiah Page, Caleb Page's son, on March 3, 1754 for 510 pounds, old Tenor. According to Caleb Stark's "History of Dunbarton," Samuel Smith eventually sold the lot to "Judge Page," as Jeremiah was later known.

(Intriguingly, a great-grandson of Jeremiah Page, born in 1783, was named Samuel Smith Page)

These were the years of the French and Indian War, which broke out in 1754 and continued until 1763. The war left Britain heavily in debt, which Parliament tried to ease through taxation of the colonies, leading to the Revolutionary War.

Many of New Hampshire's Scotch-Irish fought in the French and Indian War, helping Britain defeat France's claims to North American territory, though there is no evidence that Samuel Smith was among them.

Samuel Smith was nonetheless active in his small community and, as we will see, was acquainted with the cream of local society. In October 1760, he and Jeremiah Page were elected to a committee to maintain Starkstown's roads.

Like many of the men involved in clearing the woodlands for farms and providing lumber for new construction, Samuel Smith was also apparently involved in the local timber industry. He died sometime in 1762, leaving Elizabeth with six children.

A distant cousin now deceased, Ralph Smith, visited Dunbarton twenty years or so ago with his wife, Norma, and they were told by an elderly town historian that Samuel was drowned in a "log drive." Alice Hadley’s book cites handwritten notes by a man named Dave Tenny as saying that a Smith, evidently Samuel, drowned at Amoskeag Falls. We don't know where he is buried.

Samuel's widow, Elizabeth, was 35 at the time. He did not leave behind a will. John Stinson, one of the original John Stinson's sons, was appointed administrator of his estate on Dec. 6, 1764.

the "New Hampshire State Papers."

Both Samuel Smith and John Stinson are listed in the probate records as 'yeomen,' which in the English social order meant commoners who owned and cultivated their own land.

John Stinson was required to post a 10,000 pound bond to protect Elizabeth and her children from misfeasance. Two prominent men of the area acted as guarantors of this bond: Stephen Holland and John Stark, both listed as 'gentlemen.' A gentleman was a rung higher in the social order and was entitled to a coat of arms.

John Stinson was required to post a 10,000 pound bond to protect Elizabeth and her children from misfeasance. Two prominent men of the area acted as guarantors of this bond: Stephen Holland and John Stark, both listed as 'gentlemen.' A gentleman was a rung higher in the social order and was entitled to a coat of arms.Stephen Holland and John Stark's brother, William, were married to John Stinson's sisters. Stephen Holland may also have been Elizabeth Smith's brother.

Matthew Thornton, a surgeon and also among the original settlers in the town, acted as one of the witnesses to the bond.

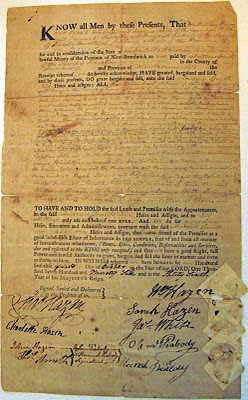

This is a remarkable document because of the signatures it contains. [You can click on the image above to see the signatures.]

Matthew Thornton was born in Londonderry, Ireland, emigrated to New Hampshire as a child and settled in Londonderry. He was among the original settlers of Starkstown, later Dunbarton. He went on to serve in the Continental Congress and was among the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Again, intriguingly, his grandmother's maiden name was Nancy Smith.

Matthew Thornton's signature appears in the lower right hand corner of the Declaration of Independence [click to see it larger]. While most of the signers signed on August 2, 1776, Thornton signed when he took his seat at the Continental Congress on November 19 of that year. You can read about him here.

Matthew Thornton's signature appears in the lower right hand corner of the Declaration of Independence [click to see it larger]. While most of the signers signed on August 2, 1776, Thornton signed when he took his seat at the Continental Congress on November 19 of that year. You can read about him here.

John Stark, too, was a larger than life figure in New Hampshire history with a dramatic life from an early age. On April 28, 1752 while on a hunting and trapping trip along the Baker River, a tributary of the Pemigewasset, he and a friend were captured by Abenaki warriors and taken to Quebec. He managed to warn his older brother, William, who was following in another canoe, but David Stinson, John Stinson's brother, was shot, killed, stripped and scalped.

While a prisoner of the Abenaki, according to John Stark's memoirs and transcripts of later interviews with the men, he and his fellow prisoner, Amos Eastman, were made to run a gantlet of warriors armed with clubs. Unlike Eastman, Stark fought his way through the gantlet and emerged relatively unscathed. The Indian elders were so impressed by Stark's courage that he was adopted into the tribe and called a "little chief." The next spring a government agent sent from Massachusetts to work out a prisoner exchange paid a ransom of $103 Spanish dollars for Stark and $60 for Eastman.

Stark and Eastman then returned to New Hampshire. You can read about it in John Stark's memoirs here.

John Stark went on to fight in the French and Indian War with Rogers' Rangers, under the command of Major Robert Rogers, another early Dunbarton settler. [Robert Rogers, by the way, once escaped a chasing band of Indians by throwing his pack down what is now called Rogers' Rock on Lake George, a place I know well. The Indians were fooled into thinking that he had fallen down the sheer rock face and abandoned their pursuit.]

John Stark later became a celebrated general during the Revolutionary War. He is best remembered for his line, "Live free or die," which he wrote in a letter in 1809 to be read at a reunion of the soldiers who fought under him at the Battle of Bennington. Stark was then too old and infirm to attend. "Live Free Or Die" is now stamped on New Hampshire license plates - ironically in a state prison factory.

Stephen Holland and John Stinson also played roles in the Revolution, but not on the same side as John Stark and Matthew Thornton, as we shall see.

Dunbarton town records show that on March 12, 1764, John Stinson sold Lot 12 in the 2nd Range to John Stark to defray the late Samuel Smith's debts and that Stark sold the property back to Stinson the following day for 3,050 pounds, "old tenor." The lot is described as "being lot whereon Samuel Smith lately dwelt, with ye buildings."

Samuel Smith's probate records include an inventory of his estate, dated Jan. 17, 1765. It was signed by Caleb Page and John Stark's brother, William. The estate was valued at 3,498 pounds, 12 shillings.

Above is an image of the inventory and below is a transcription:

Above is an image of the inventory and below is a transcription:Starkstown Jenuary ye 17th 1765There is apparently more than one copy of this inventory because William G. Stinson, in his 1998 "History of the Loyalist Stinson Family," gives a slightly different transcription. He lists the "syeth hingings" as "sylken hangings," though at only 4 pounds one wonders if they aren't some attachment for a scythe.

Honorable Sir

In compliance to your Warrant to us Dated Portsmouth December 6th 1764 We have meet this Day and Prized the Estate of Samuel Smith Deceased in the following maner as it was chewin to us by John Stinson

one Hundred acres of Land Buldings and Improvments..L 2000

one fifty acres with Common Right.............................90

one Pare of oxan.................................................198

one Horce.........................................................140

four Cowes........................................................260

one Pare of stear.................................................140

one Pare of [Ditto] year old......................................65

one stear and one Heffer.........................................50

Five Sheep.........................................................45

Five Swine........................................................100

Three chains and a clevis and Pine..............................40

Two pair Syeth Hingings...........................................4

one gun.............................................................18

two chissels one auger two gimlets...........................2/15

Four small pots old frying pan and trammel....................20

one Pare of Plow Irons and 2 Howes.............................10

Two coats and 1 waistcoat........................................60

one old Sadel and Bridel...........................................10

one old axe...........................................................3

Puter...............................................................8/7

One Beed and beeding.............................................90

One hand iron and a salt morter...................................5

Boks.................................................................12

Two wheels and one Reel...........................................9

Four old chairs and a Half bushel..................................8

Cuboards.............................................................4

one old chiast.......................................................48

Bells two Sives dear skin......................................19/10

the weddow chatty.................................................39

The above sums all in old tenor.......................L 3498/12

Caleb Page

Wm Stark

William Stinson's transcription also lists "100 books" instead of the "Boks" in this copy. If indeed there were 100 books in Samuel's possession, it would suggest that he was a fairly well educated man. In any case, the inventory suggests that he was literate.

In William Stinson's transcription "weddow chatty" is listed as "widow's cloathes."

Note that the "clevis and pine" is a clevis and pin.

Presumably some of Samuel Smith's possessions would already have been distributed among his children, but it is clear from the inventory that he was not a rich man. Given the prominence of the people involved in settling his estate, it seems reasonable to imagine that Elizabeth came from richer stock and that the connections were hers.

To put the community into perspective, a 1767 survey found that there were 271 people living in Dunbarton and 2,389 in Londonderry (then made up of the modern towns of Londonderry and Derry).

By Jan. 25, 1765, John Stinson and Elizabeth are both listed as administrators of the estate. The records refer to Elizabeth as John Stinson's wife. They were married sometime after Samuel Smith's death and Elizabeth went on to have three more children, including a son, John Stinson Jr., who many records list as having been born in 1764.

A January, 1765 accounting of the estate mentions 'receipts' of 4,470 pounds and expenditures of 1,721 pounds, 8 shillings - either from the sale of Samuel's assets or from some ongoing business.

The colonies, meanwhile, were beset by growing opposition to the crown, in particular, the Stamp Act of 1765, which taxed all legal papers, such as those filed in the settlement of Samuel Smith's estate.

John Stinson's Administrator's Account of January 15, 1767, includes charges by John and Elizabeth for the support of the children Elizabeth had had with Samuel Smith. The estate was billed 156 pounds for supporting Andrew for 52 weeks at 60 pounds a week. As of January 21, 1765, Mary and Samuel Jr. had received support for 148 weeks. As of January 14, 1767, Mary had received another 52 weeks of support and Samuel Jr. another 104 weeks.

The estate was also billed 39 pounds for the set of widow's clothing.

(148 weeks prior to January 21, 1765 would have been March 20, 1762, suggesting that Samuel Smith died around that date. Another document among the probate records charges the estate for "rates" due for 1762 and 1763, supporting the thesis that Samuel died sometime in 1762.)

The accounting was approved by John Wentworth, judge for New Hampshire's probate court and a cousin of the provincial governor of the same name.

In January 1771, Stephen Holland posted a 200 pound bond "for the guardianship of Andrew Smith, minor, aged more than 14 years, son of Samuel Smith." This date concurs with later evidence that Andrew was born in 1756. Matthew Thornton acted as guarantor of the bond.

In January 1771, Stephen Holland posted a 200 pound bond "for the guardianship of Andrew Smith, minor, aged more than 14 years, son of Samuel Smith." This date concurs with later evidence that Andrew was born in 1756. Matthew Thornton acted as guarantor of the bond.Some researchers have suggested that Elizabeth was Stephen Holland’s sister and the fact that Stephen Holland became Andrew’s guardian does suggest that Elizabeth and Stephen were related. The name "Holland" appears as a name in later generations of Smiths.

Stephen is believed to have come from the Ulster-Scot community of Coleraine in Londonderry County, Ireland, and to have returned there after the British lost the war. If he and Elizabeth were related, she may have come from Coleraine, too.

On February 4, 1771, John and Elizabeth Stinson deeded the late Samuel Smith's farm to Stephen Holland. The deed was probably in return for a mortgage because it reads, "the farm whereon I now dwell," and Holland never lived in Dunbarton. In fact, Holland was known for lending money against such collateral.

The final probate record, above, is an accounting for what remained of the estate with an order that the monies be divided among Elizabeth and the six children.

The final probate record, above, is an accounting for what remained of the estate with an order that the monies be divided among Elizabeth and the six children.It reads, in part:

1/3 of the balance (L 153/2 in new lawful money) belongs to the woman who was the wife of the deceased, and deducting interest of the two-thirds which is included makes L 106/6 to be divided among the heirs, there being six children, makes 7 shares, each single share is L 16/4 the eldest son's share being double that sum and I order the administrator to make distribution there of accordingly.[The six children included Andrew, Samuel and a sister named Mary. According to available evidence, another, older son was named Thomas and there are many indications that there was a son named William and possibly a daughter named Abigail.

Jan 31, 1771

John Wentworth J Prob

A William Smith, born in 1755, lived in Dunbarton and according to typewritten notes by Alice Hadley, she believed William to be one of Samuel Smith's sons. William and John Stinson's brother, James, married sisters. The Daughters of the American Revolution, meanwhile, list this William as having served in General Enoch Poor's brigade under the colorful Col. Moses Hazen. The DAR says he was a private in Colonel John Carlisle's company.

Caleb Stark's 1850 history of Dunbarton says that William lived on land he owned "in the valley, nearly a mile south-east of the meeting-house" and that his son Archibald and daughter Sarah were still living in the town. William, his wife Peggy, their son Archibald and daughter Sarah are all buried in Dunbarton. William's gravestone lists him as having died on May 12, 1827 at the age of 72.

Most intriguing is a note found on the Internet from another researcher stating that William had another son named Andrew, born in 1790. The name would further support the theory that William was one of our Samuel Smith's sons and brother to our Andrew Smith.

The 1880 "History of the Town of Antrim, New Hampshire" by Rev W R Cochrane, meanwhile, mentions an Abigail Smith of Dunbarton in relation to Gen. Stark. Robert McCauley, it says, "married Abigail Smith of Dunbarton, July 11, 1774 ... She called herself Nabby Smith, a niece of Gen. John Stark, and was his adopted daughter." One wonders whether this could have been Samuel's youngest child.]

By the time Samuel Smith's estate was settled, frustration over "taxation without representation" had reached a fever pitch.

British warships were stationed in Boston harbor where, a year earlier, a group of British soldiers had opened fire on a mob, killing three people and wounding others in what would forever after be called the Boston Massacre, thanks to Paul Revere's famous etching.

British warships were stationed in Boston harbor where, a year earlier, a group of British soldiers had opened fire on a mob, killing three people and wounding others in what would forever after be called the Boston Massacre, thanks to Paul Revere's famous etching.At dawn on April 19, 1775, about 70 armed Massachusetts militiamen in Lexington, Massachusetts faced British soldiers who had been sent to destroy the colonists' weapons in Concord. Someone opened fire and the "shot heard around the world" began the American Revolution.

Two months later, when British warships began shelling the hastily constructed rebel fortifications overlooking Boston on Breeds Hill (in what became known as the Battle of Bunker Hill), John Stark set off with a regiment of New Hampshire militiamen to reinforce the rebels.

His brother, William Stark (who, too, had commanded a company of Rogers' Rangers during the French and Indian War) reportedly heard the shelling from his home in Dunbarton and also set off on his swiftest horse to fight, but arrived after the battle had ended.

John Stark was rewarded by George Washington for his participation and eventually became a general. William, on the other hand, requested command of a regiment but was passed over for Timothy Bedel, a former subordinate. Apparently embittered, he became a loyalist instead and eventually joined the British Royal Army in New York.

to join the Royal Army.

In September 1776, John Stinson, Andrew Smith's stepfather, also joined the British in New York.

Another John Stinson, Andrew Smith's step-cousin (son of Samuel Stinson), had been raised by John Stark but nevertheless followed his uncle William Stark into the Royal Army.

Meanwhile, back in New Hampshire, Stephen Holland - Andrew Smith's guardian, who had also been an officer in the French and Indian War - was developing a reputation as a dangerous Tory.

All of this would have a bearing on the Smiths.

According to the historian Kenneth Scott, the Irish-born Holland (who was twice wounded in the French and Indian War) owned a tavern in Londonderry and acted as Justice of the Peace, Clerk of Common Pleas and Clerk of the Peace for New Hampshire's Hillsborough County. He had amassed a "considerable fortune" of about 10,000 pounds and held the rank of colonel in the provincial militia. Since 1771, he had served as a member of New Hampshire's General Assembly.

Scott describes him as a "good-looking, ruddy-faced, pockmarked Irishman, fleshy and five feet eight in height, was affable, popular, and a leader in the community and province."

In his 1915 "History of Rockingham County, New Hampshire and Representative Citizens," Charles A. Hazlett wrote that Holland "tarred numbers of the people with the stick of Toryism."

Holland's patriotism was publicly questioned and in April 1775, shortly after the war's opening skirmish at Lexington, he appeared before a town meeting to deny that he was a loyalist. According to Londonderry records, he said:

Whereas by mistake, misunderstanding, misrepresentation, or for reasons unknown to me, I am represented an enemy to my country, to satisfy the public, I solemnly declare I never aided or assisted any enemy to my country in anything whatsoever and I make this declaration not out of fear of any thing I may suffer but because it gives me great uneasiness to think that the true sons of liberty and real friends to their country, from any of the first mention reasons, should believe me capable so much as in thought of injuring or betraying my country, when the truth is I am ready to assist my countrymen in the glorious cause of liberty at the risk of my life and fortune.But, in fact, he had already become embroiled in a British scheme to destabilize the colonial economy by flooding it with counterfeit currency.

In "Counterfeiting in Colonial America," Kenneth Scott tells us what happened:

He was a warm friend of Governor John Wentworth and was secretly devoted to the interests of the crown.Scott mentions John Stinson of Dunbarton "among the members of the gang."

In April 1775, Governor Wentworth persuaded Holland to remain in New Hampshire and use all his arts to circumvent and disappoint the views of the patriots. The Londonderry Tory, among other acts of devotion to the British cause, organized an elaborate chain of friends and acquaintances as passers of counterfeits. Some of them went, ostensibly on business, to the southward, secured quantities of British-made counterfeit bills, and brought them back to loyalists and their wives to be passed off.

One of the gang, John Moore of Peterborough, while in Connecticut on the pretense of buying flax, came down with the smallpox in Wallingford and died there. A boy at the house where Moore had stayed, while looking for eggs in the barn, found a stone in the hay and under it a packet of letters from Governor Wentworth and other New Hampshire Toreys [Tories] in New York, some of which were addressed to Stephen Ash of Londonderry, which turned out to be a covering name for Stephen Holland. As a result of the discovery, Holland and others were detected.

One accomplice was William Stark of Dunbarton, a former captain in Rogers' Rangers and the brother of Colonel, later General, John Stark. William was also a brother-in-law of Holland for they had married sisters, Mary and Jane Stinson. Stark was indicted for counterfeiting but when released on bail he chose to forfeit his bond and fled to the British in New York, where he obtained a colonels commission.

In fact, the counterfeiting was very much a family affair. The John Moor, or Moore, whose death unmasked the scheme, was Stephen Holland's son-in-law, married to Holland's daughter Mary. For an alias, Holland used the family name of his close friend, George Ash, to whom he may have been related.

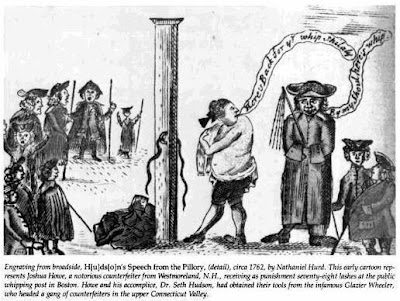

showing the punishment of a counterfeiter.

Two members of the band, David Farnsworth of Hollis and John Blair of Holderness, were arrested in Danbury Connecticut. Farnsworth confessed, implicating the wives of William Stark, Stephen Holland (Stinson sisters), among others. He and Blair were later executed in Hartford.

Scott continues:

Holland, the organizer of the band, was twice imprisoned in Exeter and twice escaped, the second time while under sentence of death. He reached the safety of the British lines and was given a well-earned commission in the intelligence service. It is small wonder that John Langdon, later governor of New Hampshire, said with reference to Holland: Damn him I hope to see him hanged. He has done more damage than ten thousand men could have done.

Langdon's feelings about the damage done by Holland are probably warranted, when one considers the disastrous effect of British counterfeiting on the American paper money. Benjamin Franklin, in an essay composed in his eightieth year, wrote as follows on the subject:

Paper money was in those times our universal currency. But, it being the instrument with which we combated our enemies, they resolved to deprive us of its use by depreciating it; and the most effectual means they could contrive was to counterfeit it.

with a warning to counterfeiters.

An historian named C.E. Potter, in his "History of Manchester," published in 1856, gives a more detailed account of the story:

The Congress held at Philadelphia, May 10th, 1775, ordered the issue of two millions of Dollars, and in July following another emission of three millions of dollars.

These bills were printed with common type, and read thus:

"CONTINENTAL CURRENCY.

This bill entitles the bearer to receive Spanish milled Dollars, or the value thereof, in Gold or silver, according to the Resolutions of the Congress held at Philidelphia, [sic] on the 10th day of May, A. D, 1775."

Of this emission, forty thousand dollars were assigned to New Hampshire, by vote December 5, of the same year.

Each colony was to provide ways and means to sink its proportion of the bills ordered by Congress in such way as its circumstances would permit, and was to pay its quota, in four equal annual installments, viz; Nov., 30, 1779, 1780, 1781 and 1782. It will be noted that the time of payment of these bills was within a month of the time specified for the redemption of the bills ordered by the colony.

On the 29th of December, the same year, Congress ordered another emission of three millions of dollars. This was assigned to the several Colonies according to population, and each was to redeem its share in four equal annual installments, the first to be paid Nov. 30, 1783.

Thus it will be seen that in the first year of the Revolution, what with the bills issued on her own account, and those assigned by Congress, New Hampshire had an indebtedness on account of paper currency of more than three hundred thousand dollars. This was an amount that would not be considered onerous in our present prosperous circumstances, but then it was alarming, and could not be met, as the result proved.

But still the bills continued at par and were readily taken in all the transactions of life. However, in January 1776, the currency began to depreciate, as the public confidence in it began to be shaken. This was mainly owing to the efforts of the Tories, sustained by the British government. These, secretly or openly embraced many of the wealthy men in all the colonies. So long as money could be had to carry on the war, so long it was evident it would be protracted, and it became the settled policy of the "enemies of liberty" to break down the currency. To do this completely, was to bring the contest to an immediate close.

Hence there was a union among the adherents of the British government to practice any means to produce to them so desirable an end. Not content with keeping hard money from circulation, and refusing to take paper money under any circumstances, they resorted to counterfeiting. Counterfeits of the various Colonial and Continental issues were put in circulation in all the colonies. These were, in most cases, the most perfect imitations. To meet this exigency, laws were passed making it an offence to refuse such currency for any obligation, and attaching severe penalties for counterfeiting the currency; but all to no purpose.

In this colony, the Tories managed with much adroitness. In January 1776, the Legislature had made the bills of the State and of the United States, a legal tender in all cases, and counterfeiting of them a penal offence.

At the same time, they had ordered another issue of paper money to defray the expenses of the war. These bills, as the others had been, were printed by Mr. Rob't Fowle, under the immediate superintendence of a Committee of the Legislature. Fowle had been gained over to the interests of the British government, and from the same form from which he had printed the money for the Committee; he struck off an immense number of bills on his own account, and that of the Tories. These were sent to, and put in circulation by the principal royalists in the colony.

Being from the same form and the signatures well counterfeited, they passed with the utmost readiness. Many of them were taken to the treasury, and received without hesitation. At length such vast numbers were in circulation, that suspicion was aroused, the counterfeit detected, and measure set on foot to detect the counterfeiters. Fearing detection, Fowle absconded, and soon after some of his confederates were detected. Among them was Col. Stephen Holland of Londonderry. He also succeeded in making his escape, after he had been arrested. Many others were more than suspected, among them men who had hitherto sustained the most unblemished reputations. They had engaged in the measure as one of policy, not for the purpose of fraud, and hence they had no scruples on the score of morality. The law of the Legislature met them however without any such distinctions, and it was with the utmost difficulty that some of them evaded its penalties.The undoing of the scheme brought financial ruin to the families involved, including the Smiths. Mr. Potter writes that "John Stinson of Dunbarton was brother of William Stark's wife, Mary. When judgment was entered at Amherst he went on bond for his brother-in-law. The sum was added to the costs of prosecution and the same became charges against the estates of William Stark when, later, they became legally forfeited."

The emission that had been counterfeited was called in forthwith and destroyed, and a new emission made. This was printed by Mr. John Melcher, late of Portsmouth, who had been an apprentice to Fowle. After the form was set up, Mr. Weare, the Chairman of the Superintending Committee, drew hair lines with a knife, across the face of the type, the bills were then printed, and the form melted down in the presence of the Committee. This device prevented the counterfeiting of this emission. This was the last emission of paper money by New Hampshire, and all former bills were called in and exchanged for Treasurer's notes on interest, and of value not less than five pounds.

Counterfeits of the Continental bills were made in England, sent over in government vessels, and distributed in large quantities. This state of the currency of itself produced a want of confidence in it, but this was greatly increased from the fact that when the time stipulated for the redemption of these bills had expired, they were paid in like currency, instead of specie.

Thus the holders of Continental bills, redeemable the 20th of November, 1779, and those holding our own Colonial bills, redeemable a month later, on presenting them had to take a like amount in paper, instead of silver. Under such an accumulation of adverse circumstances, it was not strange that the curency [sic] should depreciate. On the contrary, it is passing strange that it did not become completely worthless, long before it did.

Richard Holmes, Londonderry's town historian, recounts the episode in Chapter 6 of his 2007 book, "Nutfield Rambles."

Holland later said that the only reason he stayed in New Hampshire was that in April 1775 he had made a promise to Governor Wentworth. John Wentworth was preparing to flee the state. Holland had told him that he personally "considered it dangerous to remain in the province." The Governor convinced him to stay and "use his utmost efforts to repress the military exertions and to use every art and address to circumvent and disappoint their views, and keep me informed." And like the good soldier he was, Holland agreed to stay in New Hampshire and lie for king and country.On August 27, 1777, Andrew Smith and Thomas Smith joined with many of Holland's friends in signing a request that Holland be released on bail from Exeter, New Hampshire's "loathsome jail replete with the noxious odors of an infectious vault."

...

For two more years Holland remained in New Hampshire as a very effective British secret agent. His cover was finally accidentally blown in a way worthy of a modern spy novel. Brothers John and Robert Moor, of Londonderry, were employed hauling loads of flax from Connecticut to New Hampshire. During the March 1777 trip, John Moor took sick with smallpox and subsequently died. A farm boy went into his barn in search of chicken eggs. He put his hand into a crevice in the coop and found a flat rock where no flat rock should be. His curiosity was piqued. Under the stone he found

a bundle of letters. In time these pages were turned over to Governor Trumbell, of Connecticut, who forwarded them to the Committee of Safety in New Hampshire.

Among the letters were two that were addressed to "Colonel Stephen Ash of Nutfield." One of these said that Ash should flee to safety behind the British lines in New York. It was quickly determined that "Ash" was actually Stephen Holland. On March 11, 1777, the Committee of Safety ordered Holland and Robert Moor arrested "on suspicion of their being enemies to the liberties of America."

The request was denied but Holland managed to escape and flee behind British lines.

Once he was sprung and their cover was blown, many of the men in the Stark, Stinson, and Smith families not yet fighting for the British fled behind British lines, too, leaving their women and children to tend to the farms.

The tide had turned against the British in the war that winter, with Washington's twin victories at Trenton and Princeton after crossing the Delaware River. On August 17, 1777 - the day Andrew and friends were petitioning for the release of Holland - militia under General Stark had beat a force of Germans, Canadians, American Loyalists and Indians at Bennington, Vermont.

Family lore holds that one of the Smith brothers remained committed to the American cause and fought in the Revolution. This may have been William Smith.

involved in the counterfeiting.

John Stinson served in the Royal American Reformers. Stephen Holland served in the Prince of Wales American Volunteers. A Thomas Smith also served in the Prince of Wales Volunteers and may have been the brother of Andrew Smith.

In November, 1778, the New Hampshire Assembly moved to banish 76 men who had joined the British Army and prevent them from returning to the state without permission. Fugitives who were caught returning a second time were to be put to death. Among those named were Stephen Holland, William Stark, John Stinson Jr., and Thomas Smith.

Before the end of the month, according to Wilbur Siebert's 1916 "Loyalist Refugees of New Hampshire," the assembly proceeded to confiscate the property of 23 of the proscribed men. In each county, trustees were appointed to take possession of the sequestered estates and sell the personal property immediately at public auction, except such articles as they might deem necessary for the support of the families left behind. Stephen Holland and John Stinson were among those whose property was to be seized.

Pressure on the families didn't abate. In a petition as late as Oct. 12, 1779, citizens of Weare, Pembroke, Goffstown, and Dunbarton combined in complaining that "There are now residents in Dunbarton aforesaid, the wives and families of William Stark and John Stinson, who are gone over to the British army."

The petition said of William Stark and John Stinson that "the connection between the infamous Stephen Holland and the said absentees is well-known."

[Recall that John Stinson's wife, the former Elizabeth Smith, was our 4th or 5th or 6th great-grandmother, depending on which of the current generations you are.]

The citizens asked the new American government for relief because of the "danger of receiving counterfeit money and every evil attending spies, Lurking Villains & cut throats & murderers" because "Tories and suspected persons frequently resort to houses of said absentees and (hold) nightly and private meetings there."

"Where Settlers' Feet Have Trod."

All of this evidently took place in the house that Samuel Smith built, listed above as John Stinson's house. A notation in Dunbarton genealogy records says that John Stinson "owned and resided on Lot 12, 2nd Range. He and his son went over to the enemy in the Revolutionary war and the farm was confiscated. This was later the Straw Farm."

Another notation reads, "The farm that John Stinson and his son John owned in this town was the farm in the westerly part of the town on the road leading from the Center to East Weare and known for years as the Aaron C. Barnard farm, later owned and occupied by Charles Gourley. This was the farm that was confiscated by the Colonists during the Revolution as was that of his brother Samuel's on the North."

And yet another reads, "the dies used in making the counterfeit money that circulated during the Revolutionary War, were found in the stone wall on this so called 'Barnard Farm.'"

Alice Hadley, in her book, writes that "Stinson was one of the noted Tories of Dunbarton who caused much trouble. Counterfeit money was made on this farm and the dies found later where they had been concealed in a stone wall. The farm was confiscated."

(Norma Smith said that she was shown the house where Samuel Smith lived in Dunbarton and was told that "after it was sold a number of times, they found in the basement of the house counterfeiting equipment and between that house and the next house there was an underground tunnel.")

By 1783, the war was over and the British were scrambling to relocate the thousands of loyalists who had fled for protection behind their lines. King George promised to give land in Canada to any American loyalist who wanted it. Many loyalists had gathered on Long Island awaiting evacuation.

One John Stinson, according to Wilbur Siebert, "went to St. John in May, 1783, and became a grantee of the town, although he spent a year at Maugerville and lived later in Lincoln, Sunbury County."

We don't have the evidence on which Mr. Siebert based this claim, but he is most likely referring to the son of Samuel Stinson. The reference to May could mean that this John Stinson traveled in the Spring Fleet of 1783, an armada of ships that brought thousands of loyalist refugees from Long Island to what was then Nova Scotia.

Historian W. Stewart Wallace described the fleet's arrival in his 1914 book, "A Chronicle of the Great Migration."

On April 26, 1783, the first or 'spring' fleet set sail. It had on board no less than seven thousand persons, men, women, children, and servants. Half of these went to the mouth of the river St John, and about half to Port Roseway, at the south-west end of the Nova Scotian peninsula.Papers were circulated among loyalist refugees in Long Island seeking to estimate the number who wanted to be transported to Canada. One of these documents includes two Smiths from New Hampshire, one immediately after the other, suggesting that they were related. An Andrew is listed as a farmer from New Hampshire and a Thomas is listed as a mariner. On the document, Thomas Smith indicated that he would travel to Canada in a private vessel.

The voyage was fair, and the ships arrived at their destinations without mishap. But at St John at least, the colonists found that almost no preparations had been made to receive them. They were disembarked on a wild and primeval shore, where they had to clear away the brushwood before they could pitch their tents or build their shanties.

The prospect must have been disheartening. "Nothing but wilderness before our eyes, the women and children did not refrain from tears," wrote one of the exiles; and the grandmother of Sir Leonard Tilley used to tell her descendants, "I climbed to the top of Chipman's Hill and watched the sails disappearing in the distance, and such a feeling of loneliness came over me that, although I had not shed a tear through all the war, I sat down on the damp moss with my baby in my lap and cried."

We have no way of knowing whether these were two of our Smith brothers, but David Bell's book, "Early Loyalists - St. John," lists an Andrew Smith, farmer, from New Hampshire, arriving on the British transport vessel Two Sisters without wife, children or servant.

B. Wood-Holt’s 1990 book, “The King's Loyal Americans” also records that “Smith, Andw, of New Hampshire, farmer, disembarked River Saint John from ship Two Sisters.”

The Two Sisters was part of a convoy of 14 vessels, known as "the Second Spring Fleet," that brought about two thousand people to Canada's St. John River. Two of the ships, the Union and the Two Sisters, sailed direct from Long Island's Huntington Harbor, which had been headquarters of the British Navy since the Battle of Long Island at the start of the war. Conditions on the ships were extremely crowded, as recorded by Sarah Frost, a pregnant woman aboard the Two Sisters who kept a diary of the voyage.

On May 25, 1783, she wrote:

I left Lloyd's Neck with my family and went on board the Two Sisters, commanded by Capt Brown, for a voyage to Nova Scotia with the rest of the Loyalist sufferers. This evening the captain drank tea with us. He appears to be a very clever gentleman. We expect to sail as soon as the wind shall favor. We have very fair accommodation in the cabin, although it contains six families, besides our own. There are two hundred and fifty passengers on board.The ship didn't get underway until June, lying for much of the intervening time off of lower Manhattan.

On June 9, 1783, she wrote:

Our women, with their children, all came on board today and there is a great confusion in the cabin. We bear with it pretty well through the day, but as it grows toward night, one child cries in one place and one in another, whilst we are getting them to bed. I think sometimes I shall be crazy. There are so many of them. I stay on deck tonight till nigh eleven o'clock, and now I think I will go down and retire for the night if I can find a place to sleep.Still, the fleet idled off of Staten Island and didn't really get on its way until June 16. They reached the St. John River twelve days later and finally disembarked near Fort Howe on Monday, June 30. There was nothing there except the fort and two log cabins.

"It is, I think, the roughest land I ever saw," Mrs. Frost wrote after a visit ashore on Sunday. "We are all ordered to land to-morrow, and not a shelter to go under."

You can read more about the evacuation of loyalists to New Brunswick, here. The last British forces in the colonies, meanwhile, left New York and Brooklyn on November 25, 1783.

There are many garbled stories about the Smith brothers' arrival in Canada. One claims that they swam part of the way, another that they were imprisoned and escaped with the help of a girl. According to the strongest family tradition, Thomas and Andrew came by sea but Samuel came by land.

The most authoritative version of these tales was recorded by Nancy Melary in her book on the descendants of the youngest Smith brother, Samuel.

Family tradition holds Samuel Smith was serving in a British Army Group in the interior of the New York Colony (now New York State) where most of the troops from the General down to the last Private were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Samuel was imprisoned, although it is not known for how long, or where he was held. He was able to escape, aided by the girl who brought his meals, using a key she had hidden in the food. It is said Samuel escaped with two others, and was pursued by Patriot Soldiers. One of the prisoners was captured, but the other two escaped, traveling overland on foot to Canada and freedom.We lose track of Elizabeth's daughter, Mary. William, the presumed older son who supported the Revolution and remained in Dunbarton, is mentioned in Caleb Stark's 1860 history of the town.

"William Smith occupied land in the valley, nearly a mile southeast of the meeting house. His children, Archibald and Sarah, are still living."

Esther Clark Wright's "Loyalists of New Brunswick" lists Andrew Smith, without place of origin or mention of military service, first settling at Beaver Harbor, Charlotte County, and later at Rusagonis.

On February 15, 1785 Andrew, Thomas, Samuel Smith and John Stinson (spelled Stinsson) appear on a petition with nine other refugees asking Thomas Carlton, Captain General and Governor of New Brunswick, for grants of unsettled land on the northwest branch of Rusagonis Creek in Sunbury County.

The petition was filed by Lieut. William Dumond, late of the 1st Battalion New Jersey Volunteers. It asked Thomas Carlton, Captain General and Governor of New Brunswick, for grants of unsettled land on the northwest branch of Rusagonis Creek in Sunbury County, south of the York County town of Fredericton. [You can click on the image to see it larger.]

The petition was filed by Lieut. William Dumond, late of the 1st Battalion New Jersey Volunteers. It asked Thomas Carlton, Captain General and Governor of New Brunswick, for grants of unsettled land on the northwest branch of Rusagonis Creek in Sunbury County, south of the York County town of Fredericton. [You can click on the image to see it larger.] This is the back of the document and below a transcription of the petition:

This is the back of the document and below a transcription of the petition:New Brunswick Land Grant PetitionsThe John Stinson on the petition is most likely the Smith brothers' step-cousin, the son of Samuel Stinson.

Lieut. William Dumond et al.

To His Excellencey Thoms

Carlton Esqr Captain General and

Governor in and over His Majesties prov

ince of New Brunswick and the Terri

tories thereon depending, Chancellor

And Vice Admiral of the same &c &c &c

The Petition of the Persons whose Names are Hereunto annexed

Humbly Sheweth

That your unfortunte petitioners have not Yet Drawn Any lands who, from your Excellencey's Proclamation, Understand, that any Officer, Soldier, or Refugee may have Such lands as are Not Sittled ; and any Number of them May it by Applying

Your Petitioners have pitched on a tract of land Lying on the northwest Branch of Rosogonis Creek, which Lands have been Surveyed (Last Winter) and drawn for By the Refugees, and Not Yet Settled, and your petitioners have been informed it is given up, as there are a great Many of these lots of land Not fit for Cultivation

Your Petitioners therefore humbly Requests Your Excellency will be pleased to order your Petitioners to pick such lots on the said tract of land as they shall Think will do for Cultivation, Your Petitioners will ever pray

Rosogonis Febry 15th 1785

Wm V. Dumond Lieut

of the late 1st B. N. J. Vols.

Wm Dumond Lieut late 1st Batn N,J,V,

Refugees

Thoms Phillips

Mathew Phillips

Zopphar Phillips

Mathew Phillips Jur

James Prichard

Thoms Smith

Andrew Smith

Samuel Smith

John Stinson

[Petition endorsed, "Read in Council 2d March 1785. May advertise noting the numbers of the Lots prayd for."]

Apologies for the confusion created by the various John Stinsons. Please refer to the chart of John Stinsons above.

Apologies for the confusion created by the various John Stinsons. Please refer to the chart of John Stinsons above.This John Stinson (Andrew Smith's step-cousin and son of Samuel Stinson) was raised by John Stark after Samuel Stinson died. He was blind in one eye and, according to Caleb Stark's "History of Dunbarton," was known as "one-eyed Johnny." An interesting side story to this John Stinson is provided here.

Dunbarton town records show that on March 5, 1789, "Mr. John Stinson of New Brunswick in the Province of Linkoun, was married to Mrs. Nancy Stinson of Dunbarton in the State of New Hampshire."

The couple settled in New Hampshire and later genealogies identify this John Stinson as Samuel Stinson's son. The "Province of Linkoun" mentioned is most likely Lincoln Parish in New Brunswick's Sunbury County, putting him in the same neighborhood as the Smith brothers.

This and the appearance of Holland as a name among descendants of Thomas, Andrew and Samuel Smith - including one of Samuel Smith's sons who was named Andrew Holland Smith - also supports the thesis that these Smiths are the sons of Dunbarton's Samuel and Elizabeth Smith and became involved in the Stephen Holland saga.

The August 1785 petition suggests that Andrew, Thomas and Samuel Smith were under the charge of Lieutenant Dumond from the 1st Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers.

The following account is from a “A History of the 1st Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers.”

The Volunteers were removed from Paulus Hook in October of 1782, moving first to New York City, then Brooklyn and finally Newtown, Long Island, where they would finish the war alongside most of the other Provincial regiments then in garrison. Numerous leaves were granted for soldiers to return home and bring in their families.The entire history can be read here.

Lt. Col. DeLANCEY led a first contingent of officers and men to Nova Scotia in June of 1783, where they would search for suitable lands to settle the remainder of the battalion. The 3rd of September witnessed the mustering out of all those who wished to remain behind in New York, either permanently or temporarily. The others then set sail for "the River Saint John" Nova Scotia, which in two years time would be the new Province of New Brunswick, in modern Canada.

Here the officers, soldiers and their families received free grants of land for their service, as well as provisions for the next three years. Laws passed by the new state governments, New Jersey included, precluded their returning home, although several rank and file of little note did so without much fuss. The 1st Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers would pass into history on 10 October 1783, the official date of their disbandment, having served over seven years in the British service.

According to a history of the evacuation, "Four hundred and seventy-one heads of families were divided into sixteen companies, each having a captain and two lieutenants to preserve order, to distribute provisions, and to apportion lands."

Presumably, Lt. Dumond was one of the lieutenants in charge of the company to which the Smith brothers and their Stinson cousin were assigned.

While the petition suggests that Andrew, Thomas and Samuel Smith were civilian refugees rather than soldiers, there is evidence that they did fight on behalf of the British.

According to William G. Stinson's book on the Stinson family, John Stinson (Elizabeth's husband) served in several regiments of the Royal Army, ending the war as a Captain in the King's Rangers (commanded by Robert Rogers, the famed leader of Rogers' Rangers during the French and Indian War). He was taken prisoner in March 1781 when the ship he was traveling on to New York from Penobscot, Maine, was captured near Newburyport, Massachusetts.

A 1917 edition of the New York Historical Society Quarterly has a reference to him that reads:

John Stinson, a Tory absentee who had formerly resided at Derry and later at Dunbarton, confessed to one of the crew of the schooner Industry that he had been concerned with Holland.Stinson was jailed in Boston and eventually released on parole, but a Robert Smith who saw him in Boston reported that Stinson had repeatedly been seen "passing between New York and Dunbarton" and so Stinson was jailed again. He was transferred from place to place and was finally released in Rutland, Vermont in exchange for a "Capt. Simeon Smyth," who was being held in Canada.

He eventually made his way to Prince Edward County, Upper Canada (now Ontario), where he was granted several tracts of land totaling thousands of acres in Hallowell Township. Elizabeth and their son John Jr. followed him there. John Jr. went on to become a prominent politician, elected twice to the Parliament of Upper Canada. You can read about him here.

According to William G. Stinson's book, John Stinson (Thomas, Andrew and Samuel Smith's stepfather) died on July 26, 1813 at his homestead in Hallowell Township and is buried in the Stinson cemetery there. Elizabeth is also buried there. Her gravestone reads, "died August 16, 1796, age 67y 1m 7d. Wife of John Stinson."

Andrew and Thomas Smith remained in Rusagonis, New Brunswick, while Samuel Smith eventually moved to nearby Geary.

The following account of Samuel Smith's arrival in New Brunswick by way of Niagara, New York, is included on John Wood's wonderful blog about New Brunswick history.

I came across the following while researching for another blog post. It is from “Additions and Corrections to Monographs on the Place-Nomenclature, Cartography, Historic Sites, Boundaries and Settlement-Origins of the Province of New Brunswick”, 1906, by W.F. Ganong, which is not in copyright:Stephen Holland, meanwhile, returned to Ireland, where he died some time after January 3, 1801, the date of his will.

“Geary – I have at length been able to determine the origin of this name. The earliest use of the word I have found is in the Land Memorials of 1811, where it is called New Gary, though under 1807 it appears to be mentioned as a ‘new settlement back of French Lake’. Mr. Thos. E. Smith, of Geary, tells me the name was suggested by his grandmother, his grandfather, Samuel Smith, being the first settler there. They came to New Brunswick from the United States as Loyalists, 2nd remained for a time at Niagara, then locally pronounced ‘Niagary’. Later they came to New Brunswick, and in settling here gave the name New Niagary to the new settlement, which name became changed to New Gary, and finally the New was dropped, and it became Gary or Geary. The same explanation has been given me by Mr. Leslie Carr, of French Lake. This tradition is finely confirmed by a mention of the settlement I have found in the Royal Gazette for Apr. 14, 1818, which calls it New Niagara, and I have no question the explanation is correct. It appears as Geary in 1818 in a MS. Journal of C. Campbell.”

These are interesting details, but the finding is not new. A web page from the Archives in Fredericton at states that Geary is:

“Located 9.27 km S of Oromocto: Burton Parish: Sunbury County: settled in 1810 by Carrs and Smiths from Rhode Island and Niagara in Upper Canada (Ontario), who named the settlement New Niagara, pronounced “Ni-a-ga-ree” from which the name Geary evolved: PO Geary 1852-1959: in 1866 Geary was a farming community with approximately 40 resident families, including 6 Boone, 13 Carr and 9 Smith families: in 1871 Geary and the surrounding district had a population of 200: in 1898 Geary had 1 post office and a population of 100: included Woodside”.

The same explanation as to how Geary got its name can be found here. This site was compiled by school children who did a fine job of listing early references to both New Niagara and Geary.

The will was registered in Coolofinny, Londonderry County, on August 6, 1803. In it, Holland states that he is a Captain on half pay in the Prince of Wales regiment. He asked that he be buried "in the most private manner," "near the grave of my dear late friend, George Ash Esquire, as William Hamilton Ash Esquire may think proper."

That George Ash was possibly, or presumably, the George Ash born in 1712, who died in 1796 and was the owner of the Ash family estate, Ashbrook, which he left to his nephew William Hamilton Ash. This George Ash had an uncle named Stephen Ash, who took the name Holland from his mother, whose maiden name was Elizabeth Holland.

According to one account, this elder Stephen Holland had three illegitimate children (including twins by one of of his employer's maids), worked as a tanner, married and had seven more children - four sons and three daughters - before getting mired in debt at which point he abandoned his wife and family, went to London and then joined the army. He died while on campaign in 1712 at the age of 37.

If all of that is true, then Stephen Holland, the Tory counterfeiter, may have been one of this Stephen Holland's descendants and therefore George Ash's cousin. Stephen Holland's will suggests that he and George Ash may be buried in the cemetery of Glendermott Parish church at Altnagelvin, just east of Londonderry, near Ashbrook.

Though the Smiths arrived with the loyalists, they eventually intermarried with families that had come with the earlier British wave that displaced the French.

Andrew Smith married Abigail Tracy sometime before 1786 in Rusagonis. Her father, Jeremiah Tracy, had fought in the Revolution alongside Paul Revere, but had become disillusioned and moved his family to Canada in 1781, eventually founding the village of Tracy south of Fredericton. You can read a wonderful account of his history, by John Wood, here.

Lyle and Michael Smith, descendants of Andrew who still own his original New Brunswick farm, recount a story told to them by their Aunt Stell (also a descendant of Andrew). According to the story, Andrew stayed at the Tracy farm shortly after he arrived in New Brunswick and was so taken by their young daughter that he vowed to return when she was of age and marry her.

A handwritten list of Births and Deaths of Andrew, Abigail and their children records their marriage as July 4, 1784. The document, the original of which is in the possession of Lyle Smith's family, is of uncertain age or provenance. The penmanship suggests that it was written sometime in the 20th Century. Note that the document records Andrew's birthplace as Londonderry, New Hampshire - the only documentary proof that we have of his origins in that state beyond family lore.

A handwritten list of Births and Deaths of Andrew, Abigail and their children records their marriage as July 4, 1784. The document, the original of which is in the possession of Lyle Smith's family, is of uncertain age or provenance. The penmanship suggests that it was written sometime in the 20th Century. Note that the document records Andrew's birthplace as Londonderry, New Hampshire - the only documentary proof that we have of his origins in that state beyond family lore.Abigail would have been just 13 when Andrew arrived in the territory in 1783. She would have been 14 when she married in 1784 - giving credence to the story that he vowed to marry her when he met her and but waited until she was 'of age.' Of age was likely when she had entered puberty and could bear a child. She was 16 in 1786 when their first child was born. Andrew was then 30.

In 1796, Andrew paid 121 pounds and 5 shillings to buy eighty five acres of land with buildings along the southwest branch of the Rusagonis Creek from the Hazen, White and Peabody families.

Above is a barely legible picture of the deed.

Above is a barely legible picture of the deed.Neither Andrew nor Thomas apparently received a grant from the 1785 petition because they filed another petition in 1801 saying that since they had arrived in 1783, "no lands have hitherto been granted" to either of them. They said that they had cleared a tract of land on the Rusagonis and had built a saw mill there "at very considerable expense." This is evidently a reference to the land purchased from the Hazen, White and Peabody families in 1796. Andrew and Thomas asked for 500 acres each on the river's southern branch. This time, the request was apparently granted.

On December 17, 1808, Andrew Smith petitioned again on behalf of three of his eldest sons, Thomas, 21, Samuel and Andrew, 18, for each to receive 200 acres on the north side of the south branch of Rusagonis Creek, opposite the lands that had been allotted to him and his brother. Above is an image of that document, which you can click on to read.

On December 17, 1808, Andrew Smith petitioned again on behalf of three of his eldest sons, Thomas, 21, Samuel and Andrew, 18, for each to receive 200 acres on the north side of the south branch of Rusagonis Creek, opposite the lands that had been allotted to him and his brother. Above is an image of that document, which you can click on to read.This is a transcript:

To His Honor The President in Council

The Memorial of Andrew Smith in behalf of his three sons Thomas, Samuel, Andrew

Humbly sheweth

That Your Memorialist is settled on the South Branch of the Rushagoannis where he has resided 24 Years on purchased Lands.

That Your Memorialist lately applied for an allotment of 500 acres for himself and is desirous of settling his Boys near him.

That Your Memorialist last year built a mill which cost him upwards of L 500 and has made other extensive Improvements.